by Julia Seibert

In an industry defined by grandiose endeavors – landing on the moon, building space stations, launching enormous rockets – the efforts of young rocket startups are easy to overlook. Lurking in the shadows cast by giants like SpaceX, these companies hope to entice customers by creating cheap, innovative vehicles designed for certain market niches. Still, times are tough; in addition to a recent drop in investments for space startups in the US, the dominance of established players (like SpaceX in Western markets) makes breaking into the scene tricky. The young companies must therefore use every advantage available to them to survive, or risk following the likes of Virgin Orbit into bankruptcy.

Top Rocket Startups

RFA

German startup Rocket Factory Augsburg (RFA) seems to have realized the risk faced by rocket startups, which is exacerbated by Europe’s more conservative financial attitude towards such undertakings. Therefore, RFA is pulling out all the stops; its RFA One vehicle, a small rocket set for a maiden launch in summer 2024, is designed to lift 1,300kg to sun-synchronous orbit (SSO) at a cost of just €3 million a pop. To achieve this, the company is banking on 3D printing and (eventually) a reusable first stage. RFA is also developing Redshift, an Orbital Transfer Vehicle (OTV) that could tug spacecraft around in orbit, inspect or repair satellites, or dispose of old ones, further expanding the company’s versatility.

RFA’s plans come amidst a so-called ‘launcher crisis’ in Europe, as the continent currently possesses very little to no independent access to space. Recognizing this, the European Space Agency (ESA) is now changing its approach of procuring launch vehicles to a US-style competitive commercial approach, which RFA chief commercial officer Jörg Spurmann describes as ‘obviously perfect for us’ (as reported by SpaceNews). ESA is also encouraging companies to take part in its Commercial Cargo Transportation Initiative (CCTI) for resupply missions to the ISS, also inspired by NASA’s commercial success story. RFA is hoping to take part by means of its planned Argo vehicle, which has a payload capacity of 4 tons.

Visit company’s profile page.

Isar Aerospace

Isar Aerospace, named after the river running through Austria and Bavaria, is another German company looking to address the current European launch vacuum. Like its domestic peer, Isar is developing a small rocket – called Spectrum – capable of lifting 700kg to SSO and 1,000kg to Low Earth Orbit (LEO). The company also generously uses 3D printing for the manufacturing process (often the most expensive and timely phase of rocketry) and hopes to test reusability; still, Spectrum is set to cost at least €10 million a launch. Isar currently has agreements with both Andøya Spaceport by Nordmela, Norway and Guiana Space Centre (CSG) by Kourou, French Guiana.

Using both ports would grant the company access to polar as well as equatorial orbits. Isar is also all too aware of Europe’s need for a launch vehicle, with chief executive and co-founder Daniel Metzler claiming that the company has ‘built a rocket that will help to solve the most crucial bottleneck in the European space industry – sovereign and competitive access to space’ (as reported by SpaceNews). While past launch dates were missed and no exact date has been set, the company is aiming for a 2024 debut of Spectrum.

Visit company’s profile page.

Deep Blue Aerospace

Though China has established itself as a more than capable space power in the past few decades, its industry lacks one thing: rapidly reusable rockets. This is what its gaggle of young companies hope to tackle, most of which came about after a policy change in 2014 that allowed private actors to pursue launch technologies. Deep Blue Aerospace, based in Nantung, Jiangsu province, is one of them. In 2021, the company successfully tested a ‘hop’ of its Nebula M1test stage, in which the vehicle took off, reached an altitude of 100 meters, and landed again.

The Nebula-1 rocket, set to make its debut in 2024, is a small- to medium-lift rocket capable of putting 1,000kg into a 500km SSO. Its bigger sibling, the Nebula-1H, expands this to a maximum of 20 tons (if expended). The first stage boosters are designed to land themselves after launch, much like the SpaceX Falcon 9. Such a method would help Deep Blue rapidly reuse its rockets and lower costs. Still, competition is building up; several more established Chinese rocket companies such as i-space and Landspace are also developing similar technologies.

Visit company’s profile page.

Stoke Space

Seattle-based Stoke Space has its sights set on 100% reusability: perhaps the single most ambitious goal in current rocketry. It hopes to achieve this with its 30-meter-tall Nova rocket, a somewhat unorthodox yet logical vehicle made up of two stages. The first stage, as is currently in vogue, is designed to self-land after launch. It will also use a full flow staged combustion cycle for maximum efficiency. The second stage is where things get funky; this capsule-style craft features a single engine cycle that feeds a ring of 30 thrust chambers (as reported by Everyday Astronaut). In the middle of the ring is a heat shield regeneratively cooled by the cold hydrogen fuel circulating through the engine structure behind it. This would allow the vehicle to descend through the atmosphere unscathed and propulsively land, ready for reuse. Stoke recently successfully tested this second stage by having it perform a ‘hop’ of around 9 meters. The company aims to conduct its first orbital flight in 2025.

Visit company’s profile page.

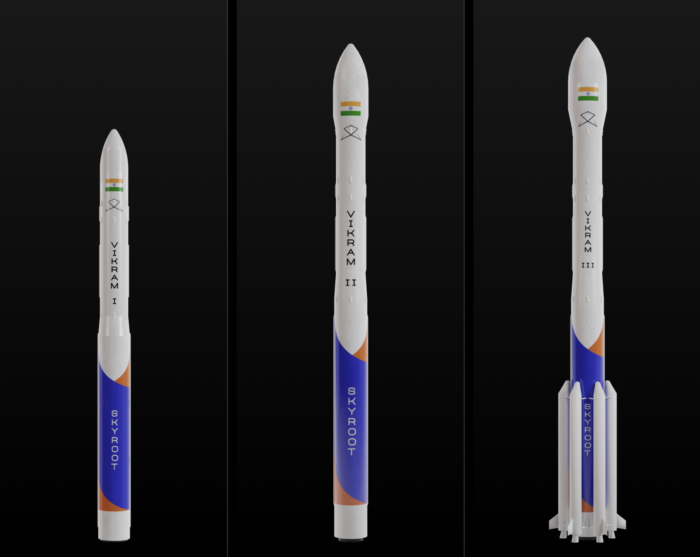

Skyroot

India is home to one of the youngest spaceflight industries in the world, as legislation boosting private involvement only came about during the early 2020s. Skyroot, based in Hyderabad, is one of its leaders. With a flight of the suborbital Vikram S rocket already under its belt – making it the first private Indian company to reach space – Skyroot is now preparing to launch its Vikram I vehicle in 2024. After that, the company hopes to launch at least two times a year.

Vikram I is advertised as being capable of lifting up to 480kg into LEO, while its larger successors, Vikram II and III, would expand this to 595kg and 815kg, respectively. All three rockets are designed to launch at extremely short notice, with Vikram I requiring just 24 hours’ notice. According to cofounder Pawan Kumar Chandana, Skyroot is aiming to provide extremely low-cost launches by means of 3D printing, using existing governmental infrastructure, and ‘the cost efficiency of operating out of India’. Reusability, he says, is also on the cards, but will take another four years or so. The company was already seeing interest from 400 potential customers in 2022, before the success of India’s space agency’s August 2023 moon landing resulted in another onslaught of messages ‘from global and domestic investors’, according to Chandana.

Visit company’s profile page.

Challenges Rocket Startups Face

Despite the promise these companies may show, most will still face certain challenges. One of them is winning government contracts, which is an often-vital stepping stone for young space companies. However, many of them might be beyond a startup’s ability, and while some schemes for smaller companies exist, it may still prove difficult to break into a market saturated by veteran companies that may have established relationships or contracts with a country or region’s government. A prime example of this is Arianespace of Europe, which is a handy tool for spreading the industry across the continent. However, it is not only one of the main causes of the current launch vacuum, but also drains ESA of millions of euros that otherwise could be used to diversify the field by contracting startups.

Commercially, SpaceX certainly poses a significant threat, which is compounded by a growing trend of satellite constellations. As satellites become standardized, cheaper, and quicker to produce, it makes more sense to pack a load of them into a larger rocket rather than launching them one by one, which is more expensive. Since most startups begin with smaller rockets, they must find a way to convince customers to spend more money on a lengthier deployment process. There are some select benefits of small rockets, such as rapid responsiveness and bespoke mission profiles, but not many companies are required to fill these niches. Winning over investors is made even tougher by the prices offered by SpaceX. Still, some startups have taken note of this and are planning to upgrade to larger rockets once the technology is tried and tested. Though prospects in this class might be better, companies will still need to deal with SpaceX’s dominance and offer some sort of innovation to catch customers’ eyes (such as specializing in certain orbits, or developing a reusable capsule like Stoke’s).

Then there are the countless problems that arise from operating any space company, including steep expenses and, more than likely, some failures. The challenge for startups is to persuade investors to put an eyewatering amount of money into technology that might take years to come to fruition, and another couple of years to turn a profit. On the other hand, developing technology too quickly can result in a few too many explosions, which might also turn investors away. Depending on the region, a single failure could be enough to kill a company; just ask Virgin Orbit.

Future Prospects

Though the challenges are sobering, they ensure that any rocket startup surviving them has a legitimate purpose in the industry, according to Chad Anderson, managing partner of VC firm Space Capital. What this purpose is can take many forms, but one significant one is geography. While they face a more challenging financial environment than in the US, European rocket startups can help provide the continent with some of its coveted strategic autonomy by means of space launches. The startups’ proposals are unlikely to pose a threat to SpaceX’s rockets in terms of their payload capabilities, but much of their promise lies in the geopolitical and local industrial benefits of having a domestic European rocket. The same goes for China, who has no access to SpaceX’s rockets and must develop its own.

Beyond these geographical considerations and the odd niche filled by small rockets (responsiveness or customizability), succeeding in the industry means going head-to-head with SpaceX. This would mean outperforming its rockets in some way, such as a higher payload capacity to certain orbits or bigger fairing size (this is what ULA’s Vulcan and Blue Origin’s New Glenn are hoping to achieve). Of course, SpaceX’s gargantuan Starship rocket would completely rearrange the industry if it becomes operational and makes good on CEO Elon Musk’s guesstimate of a $10 million launch cost (or even anywhere near that). It could not only revolutionize current launches, but bring about new industries altogether. Some more established smaller rocket companies with a particular market cornered might stand a fighting chance, but investments into many startups will probably plummet (as they likely did when SpaceX began its Transporter rideshare satellite missions). However, whether Starship succeeds in its goals and the rapid cadence needed to bring them about remains to be seen.

Many future possibilities of rocket startups depend on developments of trends in areas beyond launch considerations alone. Lunar or even Martian exploration are being eyed by several governments and companies alike, for example, which is likely to come accompanied by a swell of interest in space mining or in-space manufacturing. Such ventures might call for a dedicated rocket that a startup could build its business around. Businesses potentially created by the one-size-fits-all Starship, like point-to-point Earth transportation, could also see startups developing more specialized rockets. In addition, the US government’s high reliance on SpaceX – both in terms of launches and satellite internet in warzones – is beginning to cause concern for officials; though its space branches regularly fund other launch companies in the name of competition, this may increase if the country tries to minimize reliance on a single company.

Amidst such uncertainties, rocket startups must remember the golden rule: innovate or die. Even then, success is far from guaranteed.

If you found this article to be informative, you can explore more current space news, exclusives, interviews, and podcasts.

Featured image: Launch of BRO-8 on Tuesday, January 3, 2023, aboard SpaceX’s Falcon 9 as part of Transporter-6 Mission. Credit: Unseenlabs

Share this article: