by Julia Seibert

Big rockets get all the glory. Their glamour is undeniable; the monstrous Saturn V brought humans to the moon, after all, and those thunderous launches – blinding displays of fire, flame, and sheer power – are a sight to behold. Such heavy-lifters, however, are but the tip of the iceberg. Most orbital rockets being developed today fall into the class of small- or even micro launchers: tiny but mighty vehicles designed specifically to launch small satellites. Despite their strength in numbers, their existence is already being threatened by their bigger cousins, who promise customers cheaper, more efficient trips to space – but small launchers still have a few tricks up their sleeves. Will these be enough to survive in the ever-changing business of space?

Table of Contents

ToggleBest Small Rocket Companies

1. Rocket Lab (USA)

Rocket Lab is the undisputed king of small rockets. The company, based in both New Zealand and the US, was founded in 2006 – just four years after SpaceX – and is becoming one of the latter’s strongest competitors. Rocket Lab’s current champion is Electron, an 18-meter-tall rocket capable of lifting 300kg to Low Earth Orbit (LEO), launching from pads in New Zealand and the US. As of October 2023, the rocket has launched 41 times and deployed 171 satellites to orbit (though it is currently grounded due to a mishap that occurred during its most recent flight). Electron’s pièce de resistance is its Rutherford engines, which run on electric pumps. With these, the company claims to achieve 90% of the efficiency of traditional engines (whose pumps are powered by the rocket’s propellant) while being much simpler to produce.

Additive manufacturing, of which 3D printing plays a vital part, lies at the heart of Rutherford’s production process since churning out rockets at a breakneck pace is key to the company’s vision. ‘Every detail of Electron has been designed for rapid production to support frequent and reliable launch for small satellites’, states Electron’s user guide. Rocket Lab is also experimenting with reusability, having already retrieved a booster from the ocean and reusing an engine; the next step is to reuse an entire booster.

In addition to producing several space systems – including Photon, a satellite bus in use by NASA and manufacturing hopefuls Varda – Rocket Lab is developing Neutron, its 43-meter-tall reusable next-generation vehicle. With a tentative maiden launch date set for 2024, Neutron’s advertised payload capability of 13,000kg to LEO places it staunchly in the medium-lift category, widening the company’s customer base.

USA Honorable Mentions: Firefly, Relativity, ABL Space Systems, Stoke Space

Visit company’s profile page.

2. Galactic Energy (China)

Though the commercial small rocket revolution started as a mostly American phenomenon, China also boasts a varied, albeit younger, array of startups hoping to get in on the action.

The most prolific of these is Beijing-based Galactic Energy, which, despite its mere 5 years of age, has launched ten times (nine of them successful). So far, the company only launched its Ceres-1 rocket, a four-stage, 18-meter-tall vehicle capable of lifting 400kg to LEO. The rocket’s first three stages run on solid propellant, while the final stage uses hydrazine. Its payloads have included missions by private enterprises and a university, as well as some state-owned satellites.

The latter’s presence on the launch manifestos is especially significant given the sheer amount of Chinese state-owned rockets, including the workhorse solid-propellant small launcher Kuaizhou (operated by ExPace, a commercial subsidiary of a state-owned missile and rocket enterprise). A quick response time is a key advantage of small rockets – especially solid-propelled ones – and it seems Galactic Energy is looking to expand on this flexibility by experimenting with sea launches, which are less disruptive while providing access to a greater range of orbits.

Galactic Energy’s next project is its Pallas-1 rocket, a liquid-fueled vehicle that would launch up to 5 tons to LEO. Like the Falcon 9, its first stage features landing legs and grid fins, designed for a vertical landing.

China Honorable Mentions: LandSpace, i-space, Space Pioneer, Orienspace

Visit company’s profile page.

3. Skyrora (Europe and UK)

Europe’s commercial launch sector has long been controlled by giant Arianespace, but despite a more conservative financial climate, several small rocket companies are beginning to stake their claims in the field.

Scotland-based Skyrora is one of them. The company, founded in 2017, already has several launches under its belt. Its rockets are still in the experimental stages, with the most recent test of its suborbital Skylark L ending with a premature dip in the sea. Its new beast is the Skyrora XL rocket, standing 22.7 meters tall and designed to ferry 315kg to a sun-synchronous orbit (SSO).

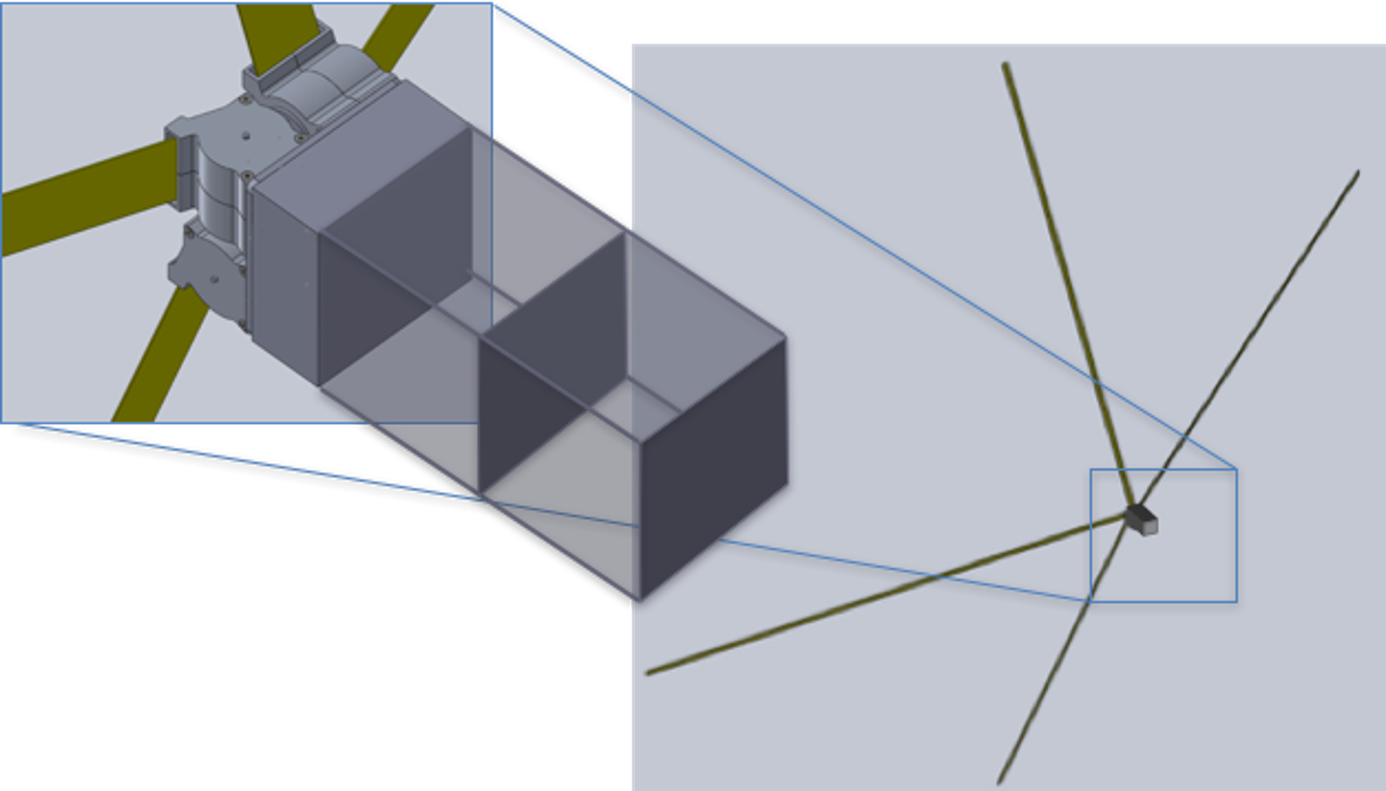

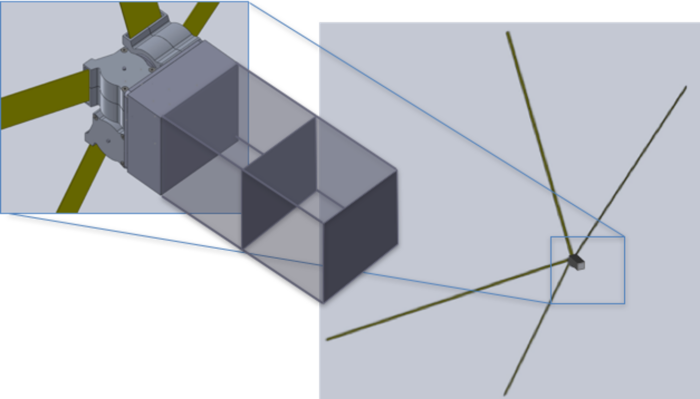

Like many of its peers, Skyrora is also structured around flexibility and responsiveness, with additive manufacturing once again playing a vital part in the production process (the company claims these printers will one day be able to work in space). A mobile launch complex, made up of modular components, is another feature implemented for flexibility. Skyrora promises ‘rapid, erectable methods of construction’ that ‘enable launch vehicle and spacecraft assembly and testing’ at a variety of sites. As for the vehicle itself, the XL’s third stage is designed to offer greater orbital versatility. A space tug based on this component is also in development. The latter is tweaked for the environment of space and will be tasked with lugging satellites to different orbits to avoid launching them separately.

Europe and UK Honorable mentions: PLD Space, Rocket Factory Augsburg, Isar Aerospace, HyImpulse

Visit company’s profile page.

4. Skyroot (India)

When the space industry began taking off, India took note. A bureaucratic reshuffle around 2020 made it much easier for a host of fledgling commercial companies to enter the scene, which previously lay mostly in the realm of government.

Among these companies is Skyroot, a Hyderabad-based startup founded in 2018. It conducted its maiden launch in November 2022 with the flight of the suborbital Vikram-S, which became the first privately-developed Indian rocket to reach space. Its successor, the solid-fueled Vikram-I, is set to make its debut in 2024, where it will launch two French companies’ satellites. The vehicle is advertised as being capable of placing 480kg into a low-inclination orbit of 500 kilometers in altitude (LEO). Later models – Vikrams II and III – expand this payload capacity to 595k and 815kg, respectively, and feature liquid propulsion on the upper stage.

As with many other small rocket companies, Skyroot is aiming to rely on flexibility, frequency, and responsiveness to catch customers’ attention, claiming that Vikram-I ‘can be assembled and launched within 24 hours from any launch site’. Skyroot also hopes to build up a twice-monthly launch cadence by 2025, which is further helped by its 3D-printing of components. Another selling point is cost; India’s space missions are famously cheap, and Skyroot cofounder Pawan Kumar Chandana claims that ‘the cost efficiency of operating out of India’ is a linchpin in lowering costs and attracting business.

Visit company’s profile page.

India Honorable Mention: AngiKul

The Rise of Small Rocket Companies

Small rockets have been around since the 1950s, but their recent heyday – which is driven by commercial companies – only came about during the last two decades or so. During the early 2000s, the US’s commercial launch sector was rather barren. Two companies – Boeing and Lockheed Martin’s space branches, who later joined to form United Launch Alliance (ULA) – and their exorbitantly high launch prices dominated the American space field. The commercial launch market had long migrated to Europe and Russia, whose (at least partially) state-run services boasted much more affordable prices. Meanwhile, the US industry was built around winning government contracts, such as launching satellites for the military or probes for NASA.

In the background, however, things were beginning to shift, and three factors in particular caused a palpable change in the US industry.

Firstly, several young, hungry space startups were popping up, and this new generation had no intention of following in their predecessors’ footsteps. Forget Earth orbit; they were eyeing up living on Mars, building massive space stations, or making space tourism as normal as hopping on a plane. The most important of these companies was SpaceX, which hoped to extend life to other planets – but to get there, they needed a rocket.

This lofty ambition eventually led to the Falcon 9, a partially reusable medium-lift vehicle that, short of being Mars-rated, turned the Earthly space industry on its head. Its self-landing boosters, which are reused after launch, save on manufacturing costs and turnaround time, resulting in rapid launch cadences and prices no competitor can dream of matching. Customers soon came crawling, and newer launch companies, taking note of SpaceX’s meteoric rise, are now hoping to siphon off some of this business for themselves.

However, SpaceX would very likely have faltered were it not for another sea change in the US industry during the dawn of the millennium: increased governmental outsourcing. The period, already marked with efforts to privatize governmental services, saw NASA looking for new ways to contract with the commercial sector, as described by The Verge. This included a shift towards fixed-price contracts, which involved NASA awarding a company a set fee to help develop a certain product or service, and, once complete, paying for it per use. The model became a godsend for both parties. NASA does not pay as much for development compared to models of the past, while the company gets a nice boost for a product it can ultimately sell to other customers outside of NASA (and is guaranteed a customer in the space agency).

SpaceX benefited heavily from this scheme; in fact, it was a NASA contract following SpaceX’s first successful launch that snatched the company from the jaws of bankruptcy in 2008. This public-private partnership has now extended to most of the US space industry, especially launches. The commercial industry, led by SpaceX, is setting the standard for low launch prices and is making orbit more accessible than ever before.

The final factor influencing today’s launch industry is the miniaturization and standardization of technology, specifically satellites. Moore’s Law, which predicts that the number of transistors per microprocessor doubles every two years, burst into the space industry in the form of smallsats: tiny, light satellites that are just as capable, if not more so, than older, bigger ones. The CubeSat – standardized smallsat units made from commercial off-the-shelf components – emerged around the turn of the century. These developments made it easier and cheaper for companies to build and launch satellites, further opening up the business potential of orbit. Their mark on the industry is obvious: 89% of spacecraft launched in 2022 were smallsats, many of which are part of constellations made up of up to thousands of them.

Smaller satellites should call for smaller rockets, then – right? Unfortunately for small launch companies, the reality is not quite so peachy. Bigger rockets like the Falcon 9 are still smallsats’ go-to for one reason: their price. SpaceX’s Transporter rideshare missions offer trips to space at as little as US $5,500 a kilo, while its top competitor Rocket Lab prices are nearly five times higher.

So why bother with small rockets at all? One consideration is flexibility. A bigger rocket like the Falcon 9 might be cheap but will dump all its passengers out in one go, meaning the satellites must either make do with where they are or carry extra engines and fuel to propel themselves into their desired orbit. Smaller rockets, meanwhile, might not be able to carry as many satellites at once but can chauffeur their payload right to its orbit without worrying about any other passengers. The difference can be thought of as taking a bus versus a more expensive cab. This is one selling point many small launchers are milking to the max, with a handful of launch companies also developing orbital transfer vehicles (OTVs) that can further increase flexibility or bring two payloads to different orbits.

Small rockets can, in theory, also be more responsive, or readily available to access space than their bigger siblings. According to Rocket Lab’s Peter Beck, launching frequently is ‘the absolute most important thing’ when it comes to increasing access to orbit. This is one downside of rideshare missions, as the launching company must wait for all spots to be filled up, whereas a small rocket is ready to go with one or two smallsats. This can make them advantageous for replacing damaged satellites or even responsive military space missions, as recently demonstrated by US company Firefly Aerospace. Smaller rockets are also logistically easier to set up and launch, requiring less extensive infrastructure than bigger ones. Several companies are working to accelerate this further by implementing supply chains and 3D printing into the manufacturing process – most notably the US’s Relativity Space – and even offering mobile launch sites for bespoke missions.

Achievements Reached by Small Rocket Companies

Small rocketry has yet to take over the commercial launch scene, which is primarily cornered by SpaceX and a few other larger launchers. Only two small rocket companies – Rocket Lab and Galactic Energy – are launching somewhat regularly, while their competitors are still finding their feet. Still, an early achievement reached by small rocket companies is their numbers: the market niche addressed by small launchers is attracting the attention of hundreds of startups. The reduced cash and infrastructure required to build and operate these vehicles – as well as a higher tolerance for risk within the industry – make it easier for companies to enter the arena. As a result, regions of the world where establishing a launch company would have been near-impossible in the past – such as Europe and India – are now seeing their first domestic rocket startups.

This phenomenon highlights another significant achievement (and opportunity) for small rockets, as Europe in particular is currently experiencing a launch vacuum. Two of Arianespace’s rockets – the Ariane series and the Soyuz – are currently out of commission, leaving only the small-lift Vega. Europe therefore has very limited means to reach orbit on its own. In the US, this problem was solved by the rise of commercial rocket companies (many of them small) and, eventually, SpaceX’s prominence. Such an industry in Europe can help address the continent’s domestic space needs without relying on a single provider. Domestic launchers could also help draw in commercial business, which is key to the UK’s goal of becoming Europe’s leader smallsat launch provider by 2030. As a bonus, small rockets lend themselves well to responsive space missions, which can support companies hoping to test out their satellites fast, or governments requiring quick access to space.

Though not a widespread achievement yet, companies in the small rocket business are using their expertise to develop bigger, more capable vehicles. Rocket Lab and Galactic Energy, two leaders in the niche, are prime examples of this. Entering the industry via the small rocket scene – compared to jumping straight into building larger, more ambitious vehicles – allows companies to gather expertise in the field (as well as funding, contracts, and a reputation) at a much lower price than tackling bigger beasts right away. They can then pursue the latter with more success (SpaceX, for example, started off with the small-lift Falcon 1 before developing the now-iconic Falcon 9).

Future Trends

Despite the rapid onslaught of small rocket companies in recent years, the outlooks are decidedly less than optimistic. Of the almost 200 small launchers worldwide, Steve Jurvetson, co-founder of venture capitalist Future Ventures, estimates 100 will fall to bankruptcy within two years. ‘You have a lot of companies chasing [small rockets]. It’s not clear to what end,’ he says (as reported by SpaceNews).

The price for the comparative ease of entering the industry through small rockets, it seems, is being stuck in a dry business already rife with fierce competition. While small launchers are theoretically better primed for availability and responsiveness, only a handful of companies are required to fulfill these needs, and the niche is rapidly filling up. Space analysis firm Euroconsult also foresees continued growth in smallsat constellations, which are easier to pack onto a big rocket rather than launch one by one. The swarm of small rocket companies must then compete fiercely for the few customers not lost to SpaceX. For another twist of the knife, the rocket business is already a notoriously perilous one as is, with many companies folding before they are fully up and running.

However, not all hope is lost. Some companies may benefit from their geopolitical circumstances. China, for example, lacks access to SpaceX’s rideshares, making small rockets a more viable option. Other companies still might use small rockets as a stepping stone to graduate to larger ones, following in the footsteps of SpaceX, which is currently effectively a monopoly. Though nobody has nailed SpaceX’s method of landing and reusing boosters quite yet (aside from Blue Origin’s suborbital New Shepard rockets), it is in the small rocket niche that such experiments are taking place.

It is hard to overstate just how much influence SpaceX wields in the rocket business; after the company’s first Transporter rideshare mission, ‘the number of smallsats launched on small launchers just fell off a cliff’, according to Fletcher Franklin, senior program manager of analytics firm BryceTech. Competitors’ complaints about SpaceX’s seemingly endlessly deep pockets and ruthless pricing are becoming an increasingly common sound in the industry.

Then there is Starship to consider. SpaceX’s still-prototypical monster rocket – the biggest in history – is designed to be fully reusable and capable of launching 150 metric tons to LEO in this configuration (250 if expended). Entire space stations or smallsat constellations could be launched aboard it at once. Such a whopping aspiration comes at a price; SpaceX founder and CEO Elon Musk estimates that the rocket could cost up to US $10 billion in development costs, with US $2 billion to be spent in 2023 alone. This suggests that Musk’s prediction of a US $10 million launch cost within two to three years might take a while to come about.

If and when it does, though, it might mean curtains for even more small rockets. While the launch price would probably be more than US $10 million, SpaceX could still offer trips to orbit at a few hundred bucks a kilo, making even the Falcons’ current bargain prices of US $5,500/kg (for rideshare) look like a rip-off. Musk’s predictions should always be taken with a grain of salt, but the Starship threat is already being taken seriously in the industry. Justin Cadman, co-CEO of space analytics firm Quilty Space, calls it a potential ‘game changer’. Abhishek Tripathi, a former SpaceX employee and current mission operations director at the University of California, Berkeley, Space Sciences Laboratory, agrees. ‘If you are not preparing for… how you’re going to change your business model to work with Starship, you are going to be in trouble’, he says (as reported by SpaceNews). Tripathi even advises smallsat operators to work with companies specializing in space tugs to get their satellites into the right orbit, so significant are the benefits provided by a Starship launch.

The issue of waiting for a rideshare to fill up before launch might still persist – especially with such a big vehicle – so small rockets may not go extinct completely. However, Musk has claimed the rocket will eventually launch multiple times a day. If Starship can get anywhere close to that – and demand persists – the space industry and the role of rockets big and small will be forever changed.

Though Starship still looms in the future, one thing is clear: in a harsh industry like this, only the strongest rockets can survive.

For more market insights, check out our latest space industry news.

Featured image: Electron rocket. Credit: Rocket Lab

Share this article: