by Julia Seibert

You might have heard that it rains diamonds on Neptune. Stories about the US $10-quadrillion asteroid 16 Psyche, made from gold and iron, may have reached your newsfeed. Lunar helium-3, vital for fusion energy, has also been making waves.

On Earth, these frequent fables of faraway riches remain a fairytale, drifting out in the darkness of space far from our home planet. The idea of mining them seems unthinkable when we struggle just to leave Earth’s atmosphere but this is exactly what a new wave of startups are gearing up to do. Breaking into the space mining industry, which is estimated to be worth US $8.19 billion by 2030, the fledgling companies must overcome significant technological and economic challenges just to break even. Whether or not they succeed could decide whether humanity has a future in space, or remains tethered to Earth.

Why Should We Mine in Space?

Incentives to mine space can be neatly summarized into three categories: supplying Earth, geopolitical competition, and aiding space exploration.

One might assume that mining a solid chunk of gold like Psyche would be a slam dunk for those hoping to get rich quick. The reality, however, is more complicated. In the long term, flooding the market with precious resources like platinum and gold would eventually crush it, rendering what is likely to become an extremely expensive effort essentially worthless. On the other hand, a higher influx of these resources could lead to previously unheard-of innovations and therefore new uses for the metals, so it is hard to say if such ventures are indeed pointless.

A more bizarre reason for space mining has to do with in-space manufacturing. A number of industries, including pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and metal alloys, could greatly benefit from manufacturing their products in space. Factors such as a microgravity, sterility, and a vacuum state help spread materials out more evenly and also remove impurities, making the products superior to those produced terrestrially. But launching all that infrastructure, not to mention the constant resupply missions, could result in the process being costlier than it will already be. If technology progresses, using material mined from space could become key to this emerging industry.

Geopolitics have a part to play, too. Rare earth metals and platinum group metals (PGMs), which are at the heart of countless technologies including semiconductors and catalytic converters, originate almost entirely from China, Russia, and South Africa. To reduce reliance on these sources, especially with mounting political tensions, countries without such bountiful ground might one day find it worthwhile to source their metals from the solar system, according to AstroForge cofounder and CEO Matt Gialich. This also goes for rich states whose economies depend on one commodity, including Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Both nations are planning to diversify their economies, with the UAE making an active effort to attract space mining business.

All of these benefits and more means that mining might prove vital to sustaining faraway human colonies too distant to rely on resupply missions launched from Earth. Mining water for consumption and even breaking it down into rocket fuel is one example. Extracting certain materials from regolith to build structures shielding colonists from radiation is another. In a nutshell, mining celestial bodies is the only way to ensure a colony can remain independent from Earth and greatly increases its chances of survival.

Risks of Space Mining

It sounds peachy written out like this, but space mining is about as tentative an industry as they come. One big risk associated with it is the economic one. Planning, building, launching, and operating all this largely untested technology will take years, if not decades, and seeing a profit could take even longer. In other words, investing in space mining requires deep pockets and a lot of patience.

Before the new generation of mining startups popping up these days, a number of companies tried and failed to break open the industry, floundering in the face of economic hurdles. Among them were Made in Space, Deep Space Industries, and Planetary Resources; the latter two in particular ‘did not deliver on their promises to investors,’ according to Chad Anderson, CEO of space-focused venture capital fund, Space Angels. They were eventually absorbed by other companies, and their mining dreams ceased to exist.

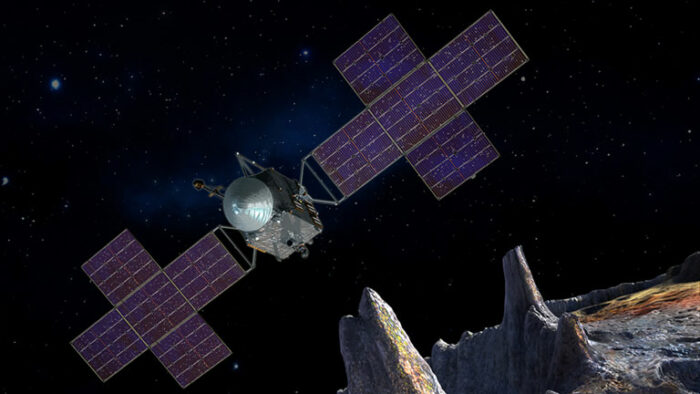

With the first extinction event of space mining behind them, newer companies face a further developed industry, but mining celestial bodies remains one hard nut to crack. Previous governmental efforts such as Japan’s Hayabusa missions managed to harvest some dust from asteroids and return it to Earth, but the samples were tiny. Hayabusa2, which dropped its sample off in 2020, returned 5.4 grams from its target asteroid Ryugu, and even that vastly exceeded expectations. If the new startups are serious about space mining, they are going to need to step it up a notch.

Assuming the economic and technological obstacles are overcome, yet another risk presents itself: politics. Space mining is an iffy subject when it comes to UN space law. Essentially, this dictates that nobody can ‘own’ a celestial body, or lay claim to a part of it. But these laws are vague, outdated, and therefore easy to manipulate, which could result in political squabbles. What happens, for example, if a country decides to harvest the resources of an entire asteroid for profit?

Much of space exploration is driven by politics as it presents a good way to demonstrate technological superiority over one’s enemies, and space mining is already exacerbating this. In an effort to foster the space mining industry, several countries – including the US, the UAE, and Luxembourg, of all places – have all created laws allowing companies and individuals to own objects brought back from space. This already tests international law, and the process has not even kicked off yet.

Technology Used for Space Mining

The first step in space mining is identifying what object to target. More often than not, these would be asteroids, which are tiny, dark, and generally tricky to spot with a telescope. Figuring out what resources it contains – water, metal, rock – is even harder. The long-dead Deep Space Industries had planned to tackle this issue by sending tiny spacecraft, dubbed ‘fireflies’, to promising asteroids to scout their riches. A similar process had been envisioned by poor old Planetary Resources, who also considered using a designated telescope to peer at promising suspects.

Once a suitable asteroid is found, the next step is deciding what to do with it. Approaching the celestial object, mining it, and leaving again is one option. However, there is a case to be made for towing the whole asteroid closer to Earth, since shipping all that heavy mining equipment into deep space and back might require more energy than just using a simple tug to bring back the entire thing. This also minimizes wasted material. Plus, this makes the process safer, since unintentionally changing an asteroid’s orbit while trying to mine it could spell bad news for anything in its path. Placing it in a stable orbit close to Earth minimizes the risk of an accidental reenactment of Armageddon.

Next up in the mining process is, well, mining. Depending on the resource in question, this can take on several different forms. For harvesting metals, the obvious option of drilling comes to mind. But while this could work on the moon and Mars, asteroids’ weak gravity makes this difficult. Instead, magnets could be used to pluck metals from the rock. Biomining – using bacteria to extract metals – is another option, and this process has even been proven to work aboard the ISS. Simply hoovering up rocks from the surface and refining them onboard a spacecraft has also been suggested.

Water, to be used for extraterrestrial substance and rocket fuel, will become comparable to liquid gold once space exploration takes off. It is often found in stony C-type asteroids, which, as opposed to the more metallic S and M-types, are so crumbly that its rocks could be crushed by a human hand. One could simply scrape to surface – a process known as strip mining – and collect what comes off. This could be done through mining bots who dock to the asteroid and suck up the water-rich surface debris, which would then be heated up to extract water in vapor form. A more direct approach to this is optical mining, wherein the entire rock is enveloped in a waterproof bag. Concentrated sunlight is then used to toast the rock until its water content evaporates from it to be collected in the bag.

While ideas like the above are constantly being tossed around, it is important to remember that they are still highly theoretical. The companies below hope to change that.

Promising Companies Developing Space Mining

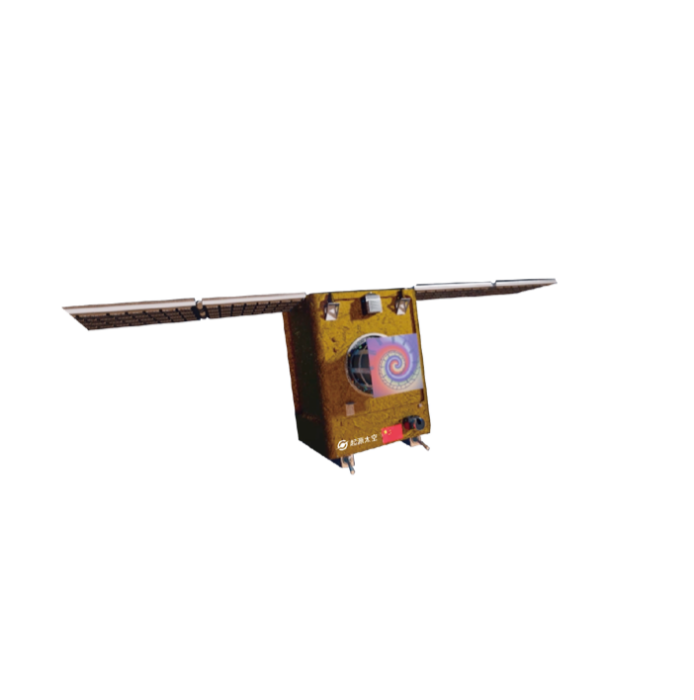

Origin Space

Origin Space, a company based in Nanjing, China, seems to be the frontrunner of the new rise in space mining. In April 2021, the company became the first to launch a commercial craft dedicated to testing space mining technology with its NEO-1 satellite. Yangwang-1, a telescope designed to find suitable asteroids, monitor space debris, and survey the skies, launched two months later. Origin also has a lunar rover in the works, with which it hopes to conduct ‘commercial exploration of lunar resources and verification of mining technology’. This could include seeking out possible sources of water on the moon, or harvesting Helium-3, an isotope abundant on the lunar surface that could prove instrumental to fusion technology.

Visit company’s profile page.

AstroForge

California-based startup AstroForge has a big year ahead. The firm’s ultimate goal is to mine PGMs from asteroids, and its first mission is set to launch this month. The craft itself, a mini-refinery called Brokkr-1, is a simple Cubesat with material mimicking asteroid rocks onboard. The aim is for the company’s refining technology to be put to the test extracting metals from the rocks. Onboard the Cubesat, the material is superheated and vaporized, then sorted into its ‘elemental components’. Later this year, the company’s second mission is to launch, this time with the purpose of scouting for juicy targets. Here, a larger spacecraft known as Brokkr-2 will pass by a small asteroid to check whether it is indeed the metallic M-type AstroForge expects.

Visit company’s profile page.

TransAstra

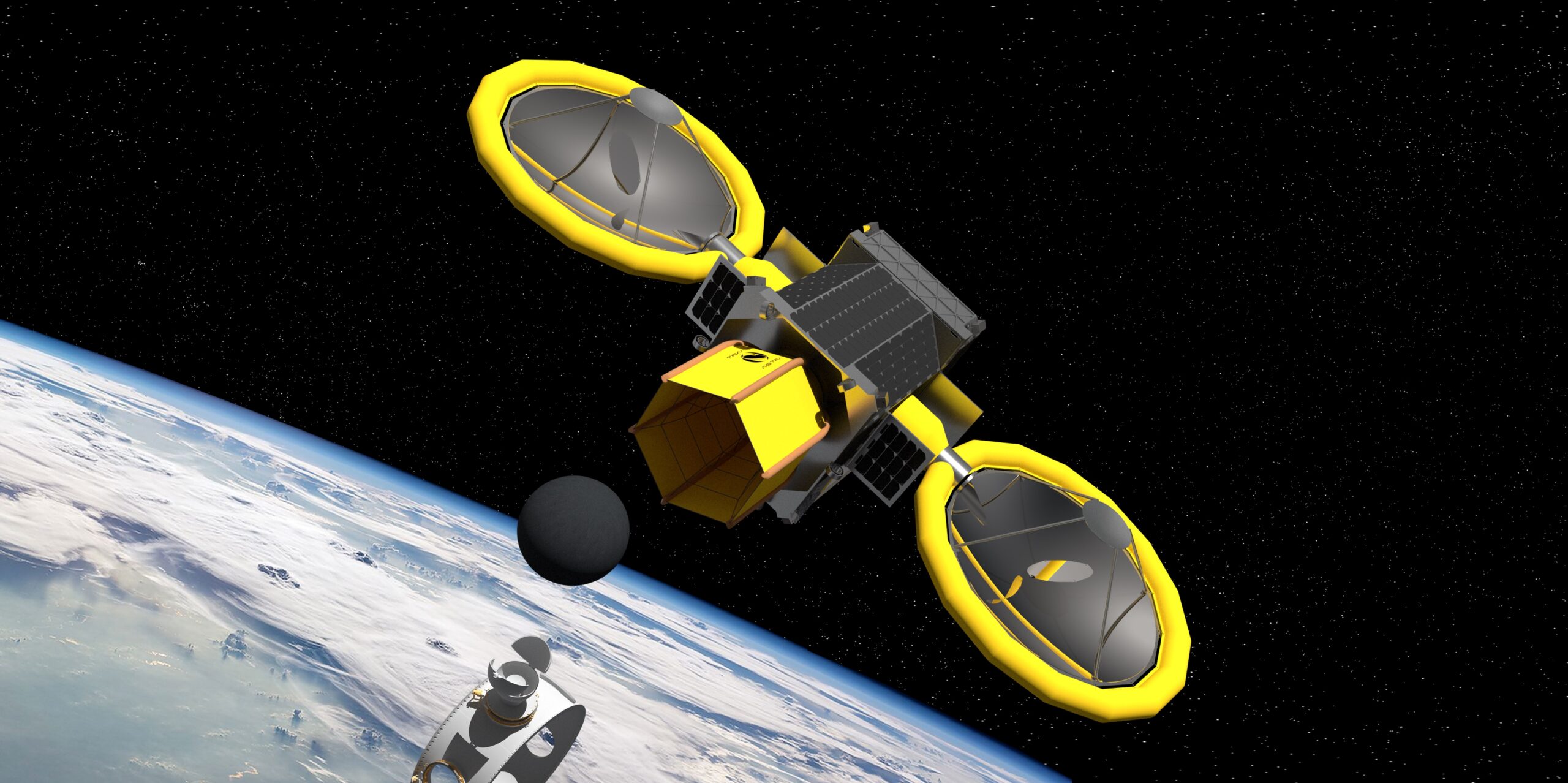

While AstroForge mines metals, TransAstra sets its eyes on harvesting water. The Los Angeles-based startup is currently focusing on sustainability and debris removal, but is developing a multi-stage optical mining system based on similar technology. The company’s Sutter telescope, already partially operational, provides the first step of the process of scanning the skies for lucrative targets. TransAstra then hopes to fit their Worker Bee space tugs with optical mining equipment to create a technology demonstration craft called Mini Bee. This will be followed by the industrial-scale vehicles Honey Bee and eventually Queen Bee, the latter of which the company claims will extract thousands of tons of water from C-type asteroids. Still, with the company’s focus on space debris for the moment and no launch dates set, it could be a while before this becomes a reality.

Visit company’s profile page.

Helios

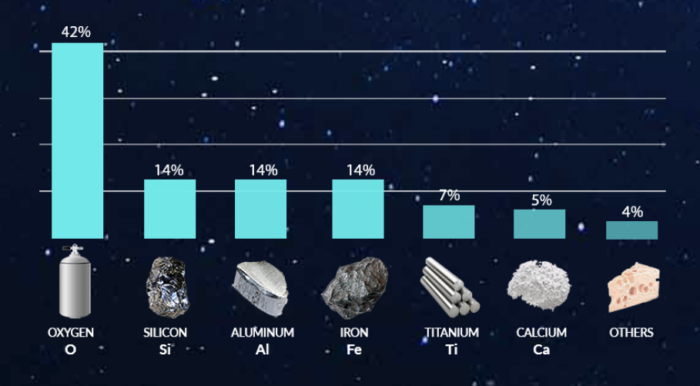

Helios, based in Israel, is eyeing up yet another valuable resource to be harvested from space. Oxygen is vital to powering many rockets, and makes up a large part of their mass. But for deep space exploration and colonization, missions would require more of it than is convenient to lug to the moon and beyond. Helios figured that since the element makes up 45% percent of the moon’s soil mass, extracting and distributing this could not only enable further exploration, but make them a nice bundle too. Their envisioned extraction mechanism, the Molten Regolith Electrolysis (MRE) reactor, would heat up the regolith and separate the oxygen from other elements such as iron. The oxygen could then be used for spacecraft already on the lunar surface, but might also be shipped anywhere in between the earth and the moon, enabling longer and more efficient missions.

Visit company’s profile page.

Ain’t Space Mining Too Expensive to Bear Profit?

While it is true that it will be a long time before space mining becomes profitable, a few things have changed since the previous generation of mining startups met their fate. First, technology has evolved quite a bit. Increasingly affordable launches drive prices down and lower the barrier to entering the game. Cubesats have seen leaps and bounds in development, and integrating payloads into the small, cheap satellites can help mining companies drive preliminary mission prices down even further. In the future, planned heavy lift vehicles like Blue Origin’s New Glenn and SpaceX’s Starship would be able to carry heavier infrastructure, possibly even mining stations, to space at somewhat affordable prices.

In addition, younger companies are learning from the demise of the previous generation of mining startups, looking for clues on how to avoid a similar fate. The doomed ventures focused on making a dime early on in the game, which is simply impossible with a long-haul development process like space mining. As a result, they failed to deliver on timelines promised to investors and went bust. AstroForge, for one, plans to avoid this. “We are a company that is 100% mission-driven on mining an asteroid and there are no intermediate revenue streams,” says CEO Gialich. “We either mine an asteroid or we fail.”

Another thing to consider is that geopolitical competition might accelerate the space mining industry. Chances are, as soon as one world power starts mining, others will rush to follow. One country having a monopoly on anything, including space-based resources, is something that its adversaries would want to avoid. Already, American officials are shaking in their boots at the idea of China landing on the moon and establishing a base there, arguing that the latter will claim our nearest neighbor for its own. Like in an arms race, the prospect of a power colonizing space could be enough to propel the other to do so as well, and space mining is a vital part of this.

When Can We See It Coming?

With so much unproven technology, it is hard to gauge when space mining will become commonplace, but preliminary processes have already begun. Experimental missions like those of Origin Space and AstroForge lay the groundwork for a commercial mining industry, which could take decades to come about due to the long wait for returns on investment.

At the same time, government agencies like NASA, are hatching lunar plans spurred on by geopolitical competition. Lunar colonies, like those envisioned by the US and China, will likely depend on using locally available resources to sustain colonies in a process known as In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). Space mining is at the heart of ISRU as it involves extracting water and oxygen from regolith, or even building entire structures from it. Both countries’ manned lunar missions are set to start by the end of the decade, with mining projects likely to follow.

Our Take on Space Mining Companies

Space mining could go one of two ways. The obstacles involved might mean it never materializes, killing the industry before it even kicks off, and hindering extraterrestrial colonies from developing beyond basic outposts. If the risks pay off though, it could revolutionize a number of Earthly industries, create new ones in space, and help bring about thriving, maybe even independent colonies. Simply put, space mining could make or break a future in space, and that weight now lies on the shoulders of a few humble startups. Could they build the groundwork for the beginnings of a new era in space? Or will space mining remain just another space age fairytale?

Featured image: Illustration of the Mini Bee mission concept, a 2019 NIAC Phase III. Credit: TransAstra Corporation

If you found this article to be informative, you can explore more current space news, exclusives, interviews, and podcasts.

Share this article: