Pulsar’s first episode featured Zaria Serfontein, who has a bunch of work titles, job titles. One of them is being the Bid and Mission Concept Engineer at Astroscale. She’s also the co-founder of Frontier Space Technologies and the chair of UKSEDS (UK Students for the Exploration and Development of Space). This is an excerpt of the interview that you can listen to in full here.

Ria: Can you just walk us through your life and introduce yourself to our listeners, just tell us where you come from where you are now? And basically start with your childhood.

Zaria: I am originally South African. I was born in South Africa. I lived there for about 12 years before moving over to Ireland. I think the growing up, I don’t think I realised that space existed, South Africa is kind of very focused on South Africa, because there’s a lot going on there. So it’s, it’s not really the land of opportunity. So you know, as far forward as I could think it was just basically, you know, I want to go to university, that was kind of the photos that I thought ahead. When I moved to Ireland, there was a few more opportunities. But I also went to an all girls Catholic secondary school. So some of my choices were things like Home Economics, or art or music. So not really the engineering, technical drawing things that I might have been interested in. But it was still good. I did physics, art and geography. Just to show you how confused I was at that point of what I actually wanted to do.

And actually, I did much better in Irish than I did not. I did so poorly in that setback that I had to do a special exam over the summer to even get into my university course to be able to study engineering. So on paper, it did not look like I was an engineer. But in my head. I knew what I wanted to do with engineering. I wanted to build things, fix things, pick things apart, learn how to work.

Ria: You have a bachelor’s in engineering, in aeronautical engineering, you have a master’s in Astronautics and space engineering. And you are currently doing a PhD in aerospace aeronautical and astronautical space engineering. After your masters, you chose to go for a PhD.

Zaria: I chose over the course of a year ago for a PhD. So I moved over, did the space engineering Master’s. And then, you know, was completely thrown into this whole new world of space. I did. My first week, we studied astrodynamics. And I had this stupid idea that it was going to be any way shape or form similar to aerodynamics, where like, you know, astronautical aerodynamics, they must be connected somehow. Completely wrong. But, you know, completely, just just so much new information to take in. Yeah, so much to do. And then, after that year, it was like, Okay, what’s next? You know, do I take out a job? Do I study more? Do I go back into aerospace. And what happened was, I could only find a job in aerospace, like, I could only find a job in these aerospace roles, where they couldn’t guarantee that you’re going to work in the space sector, you know, you might end up working in aviation, you might end up working on transport, things like that. And that’s not what I started my master’s for, you know, I really, really just wanted to work in the space sector. So it was a lot of going back and forth. On like, if I do a PhD, am I like overqualified for some of the jobs that I want, you know, will I be able to go back to the industry, if I don’t do that, and I take an aerospace job, I’m gonna going to get stuck in a certain sector and not be able to transition over. So I had like a gap year almost where I was a research assistant for a few months. And that kind of gave me time to figure out what to do next. But the opportunity for the PhD was that the my supervisor was saying to provide with my master’s, she was amazing, so supportive, and she helped me kind of create the PhD that I wanted to do. And I kind of saw just as three years, building up all those skills that I didn’t have at that point, that meant that I wasn’t getting jobs that I wanted. So I had like a mental list of like, picking up systems engineering, and testing and all of these kinds of things over three years, and then, you know, eventually ending up hopefully, where I wanted to be.

Ria: In the UK, a lot of space related jobs are strictly connected to the RAF. So the Royal Air Force, so you can get certain jobs unless you’re a UK citizen, or unless you’ve been in the country for at least five years, so they can do all the background checks. Was that the case with you? Have you had any trouble getting a job because of that? Because you haven’t been in the country for long enough?

Zaria: So I think that would have been the case if I was South African 100%. Because the UK invaded Ireland a number of times and very bad things does, it means that a lot of the legislation around like being able to work in different countries and stuff like that, Irish people get like a certain exemption to that. So luckily for me, it meant that because I had an Irish passport, I could work here without having to jump through all those hoops. But there are a lot especially like you said because of how close is linked to the defence sector.

Ria: You’re the chair of UKSEDS, which I’m a member of as well. So what do you do there? What does UK says doing? What do you do?

Zaria: UKSEDS it’s a set it’s is this global organisation students for exploration and development space and there’s different chapters in different countries. And the UK happens to be one of the oldest ones because we’ve been around for about 35 years. And then the other ones are you know, there’s one of us that’s very active SEDS Italy is very active. We’re about a week away from our biggest event of the year, which is the National Student Space conference. That’s where we bring about 500 students together to just network with everybody in the state sector, do workshops, go to panels, socials, everything like that. We also run a lot of different competitions to help students get the skills that they need to get into the space sector, because we’re kind of that point, bridging people who students to the actual space sector, and what we hear a lot from industry is, you know, the students don’t have the right skills to enter the space sector, they don’t have the practical skills they need, they have theory, but they haven’t find it. And from students, we’re here to say we’re like, here, there’s just no opportunities to actually get hands on with a lot of these projects. So we try to get them to design and build rovers, rockets, satellites, you know, just very low risk, you know, you can make a lot of mistakes. And then you can, if it blows up in the end, it’s fine. Yeah, basically, we run a lot of those events. We also have space careers, where you can learn all about careers in the space sector, that’s going through major redevelopment at the moment. So we’re trying to make it a bit more sustainable and professional. Then yeah, apart from that, there’s just so many other small things that we get involved with as well. We just tried to be the voice for students amongst industry. And we tried to make sure that every opportunity that the industry has, we’re flying back down.

We have between 50 and 100, very active volunteers. So these volunteers are the ones that do a lot of real work. They’re the ones that put together to competitions that put together do events that, you know, help us write papers about the sector, anything like that, and everything, and are kind of split into different teams. So we have outreach, we have diversity, we have competitions, we have membership, anything like that. And then every year, we elect an executive committee that is made up of six members, and they’re the ones legally responsible for the charity. And they’re the ones also a bit more focused on long term strategy. And although it’s difficult as six students to decide what the future long term strategy of the charity should be, but it’s basically just a longer view on what UKSEDS could be doing, and building up a lot of those kind of industry connections as well.

Ria: And then you went on and became the co founder of Frontier Space Technologies. How did that happen? And what does frontier space do?

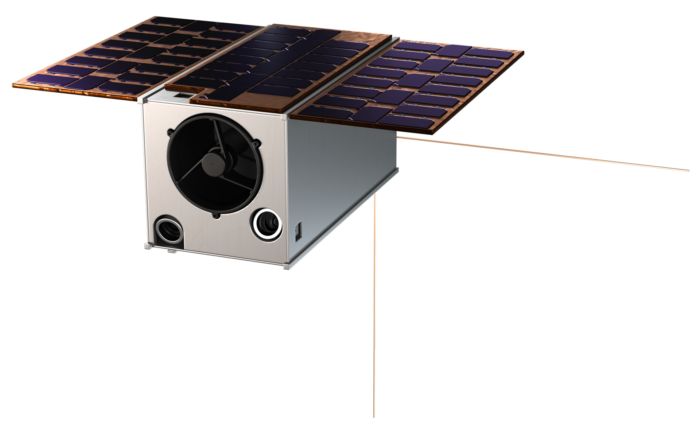

Zaria: When I was doing my PhD, I was working on a device that’s going to help satellites do orbit a bit quicker. So it’s one of those kind of cool space initiatives. And there’s a product there, that as an academic, as a PhD student, I was just finding incredibly hard to actually give to people. It was it was a case of, you know, I noticed technology exists. I know it can help a lot of people be more sustainable. I have a way to make it really cheap. I have a way to make it really adaptable to different satellites. But just the physical act of actually being able to commercialise it just wouldn’t be possible without having like an entity to sell it. And so the opportunity came along where there was already three co-founders country space technologies, who were spending out technologies at a company University, and they invited me to join so I think at the moment we’ve shifted focus a little bit so we’re not so much on drag sales anymore. They still exist, do you want them but we’re more focused on this miniaturised lab that we’re sending to space so you can do microgravity experiments in space.

Ria: How big the problem of space debris is, according to you?

Zaria: I think the difficulty is, there’s so so many variables, when it comes to space. The models that we currently have to predict how much space debris is up there to predict how much worse it’s going to get to, you know, to even track pieces of debris, we’re just not there. We can’t we don’t have an accurate estimate of what’s out there, we don’t have an accurate estimate of how much worse it’s gonna get. And because of that, it’s really, really difficult to get that sense of urgency across. Because even if it’s the case that you know, it’s not going to be an incredibly huge catastrophe within the next 10 years, if we don’t start fixing it now, it’s going to not be possible to stop it at all. But it’s difficult, especially because space sector is developing. So there’s a lot more industry now there’s a lot more new players. And when you’re thinking about business, you need to think about profitable profitability. I

Ria: You also work for Astroscale, and Astro scale is trying to do something similar, and de-orbit satellites in a different way. Can you tell us how you landed the job? And what you do there?

Zaria: Astroscale is looking to do a bunch of different things, but mostly focused on like active debris removal. And so being able to remove satellites from orbit or being able to remove pieces of junk from orbit, and then, you know, all the kind of adjacent sectors that that include as well. So things like looking at refuelling or things like looking at being able to swap out modules, satellites, and to make them live longer. Anything like that. And in orbits everything. But yeah, I actually got the job because I UKSEDS. I think I’m partially because, you know, I qualified for it. But I think mostly because we’re networking, one of the trustees at UKSEDS works at Astroscale. So I was able to talk to him a lot about it, talk to rules, and saw him at different conferences. I’m sure he prepared a good word for me as well, which goes a long way. But yeah, I think it’s getting better. But I think just a sector is quite, you know, still growing, still developing. So the more people you know, and the more people who know that it’d be easier just to get it.

Ria: And what do you do as Bid and Mission Concept Engineer there?

Zaria: I’m an engineer, but I’m working on the business development team. Astroscale is still technically kind of a startup, you know, making money but are still technically your startup. So we have to still apply for a lot of these government bids, and these larger bibs. And to be able to do that, we need to convince them that we have a really good product. And there’s a lot of technical work that goes into putting in a proposal we’re putting in a bid. And you know, the engineers are focused on actually building the next satellite evolving the next piece of equipment that we have. So what I do is I work with the engineering team, I work with the business development team. And I’m almost like that bridge between the two.

Ria: What do you think the solution in the long run is to the space debris problem?

Zaria: There’s regulations, regulations are still incredibly important, but to be able to implement them at an international level, which is needed, because space is so international, it takes a very long time. And that’s why things like the 25-year rule, where you have to do orbit within 25 years after end of life, that’s why that hasn’t been shortened yet, because it’s just very, very difficult for every everybody, every spacefaring nation in the world to agree that, okay, this is gonna be to me your number. But it’s still important. So it’s still important for the UN space, physical space agencies to work together to implement that. So that’s one side. And the other side is that the NewSpace, so the phase companies that are in part of agencies that are using this for commercial benefit, they’re growing a lot quicker than the space agencies are. So those like 1700 satellites that you said, were launched last year, probably like 80%, if not more of them, were commercial satellites, you know, they’re starting to, they need to make a profit. So for that, you know, keeping, introducing stricter guidelines isn’t necessarily going to work. It’s more about getting across the idea that it’s beneficial for the companies themselves to have a cleaner space environment, because we’re doing a lot of studies on to show that like, to be able to avoid debris is costly, because you have to, you know, move your satellite out, where you can use propulsion, propulsion of mass, mass is expensive. You know, it’s it’s expensive to live in an environment that’s polluted, and you’re risk, you know, your satellite that you spent years developing, you know, building launching all of those costs, they could just be gone in an instant. So for that, it’s more about business practices. So it’s about making sure that the new players in the space sector understand that, like, it’s beneficial to them to be more sustainable. And so that’s kind of like the agency side, we still need to regulation side, we still need the business side. We still need to clean up what’s there currently, because that’s also going to keep getting worse. So that’s the active removal site. But it’s difficult to know because it’s all of these things together. And then on top of that, that there’s a layer of us just not knowing what’s out there. Like that’s still waiting to be developed because there’s all this talk about space traffic management, which is basically setting up basically rules of the road. It’s like trying to it’s a motorway up there, but there’s no lanes. So we’re just trying to put in my, we’re trying to put in rules. But it’s hard to do that if we don’t know where to things are or that so. The best thing we can do is removed future space. And at the moment, the best way to do that is by the orbiting, but a very recent paper that may or may not be discussed at the next national students is suggesting that the burn up is also changing the composition of the atmosphere. And that is actually making it harder for things to de-orbit. So as much as you know, the idea of let’s burn things up so that we can get rid of the junk in space because that sacred space, it’s going to make it harder long term to be able to do orbit things.

Ria: How do you see the future of the space industry? Is it worth investing in? Is it worth studying to get into the space industry? What can you say about the future?

Zaria: I think I think the space sector is growing faster than in any sector I’ve been a part of before. And it’s getting much wider as well, which is both great and a problem. Because in the space sector, we tend to rely very heavily on people joining the space sector, because they’re, they love space and are interested in space. And then maybe not putting that much effort into making sure that the working hours are convenient, and that we give good holidays, and that we pay very well. And so I think, I think the space sector is super exciting. And I think there’s a lot of people want to join it. But I think we also need the very standard, you know, administrators, we need IT support, we need all of those kinds of things that we’re maybe not catering to well for at the moment. But it doesn’t mean there’s a lot of gaps there. I think in the industry sector, one thing we constantly hear from industry is that they just can’t find the right people. You know, we need people from other sectors to decide to join the space sector and to decide to join us. But it’s definitely very, very exciting. We’re sending the satellites into be worst place ever, space is not a place you want to be. It’s cold, there’s radiation, debris, you know, it’s terrible. And then, you know, they still work, we can still get photos back from Pluto, we can still, you know, go back to the moon, we can still send satellites up, that’s helping us, you know, solve the climate crisis. So, I think, so much scope for it so many jobs out there. Never think that it’s elitist, I think we’re just very, very bad at talking about it. It’s not like a space than to just I know, as a PhD student, it’s not for me to say, but it’s not just PhD students, and like these genius people, it’s everybody, we’re just very, very bad at talking about space.

Ria: What’s needed the most in the space industry? So what do you need more engineers? Or do you need, I don’t know, designers? What’s urgent?

Zaria: I think there’s always going to be a demand for the engineers, because at the heart of everything we do is, you know, the rockets, satellites, you know, getting to space designing payloads, things like that. But I think there’s a lot more draw, as well, for these kind of adjacent sectors. So regulation you mentioned, and I think that’s going to be huge in the next few years, anything to do with policy changes. In the UK, especially, you know, we’re launching our own satellites for the first time from UK soil, and that involves an incredible amount when it comes to insurance and licensing. And, you know, developing that whole system, like it doesn’t, it doesn’t exist, you kind of have to create it out of nothing. So, as an engineer, definitely enough engineering jobs, especially if you can do anything with software, because software engineers are gold, and we have to compete with every other sector for them. So if you’re a software engineer come to us. But the Yeah, engineers giving as well. And then there’s the other huge sector, which is operations. So ground stations, you know, being able to control the satellite, we have to babysit them so much, you know, just to make sure that they’re not flying into anything or doing anything strange. So being able to do that from work as well.

Ria: Would you go up into space?

Zaria: I would go, I’ve been asked this question. I have no idea why. But I just have this, I have this huge desire to go to space, even though as part of an analogue astronaut mission before I found that everything that can go wrong with you in space. I know when you first get there, you’re going to be incredibly nauseous, you’re going to feel hungover, all the blood is going to rush to your head because your body is pumping blood at the same speed but it’s you know, gravity is not there. Your eyesight will come back permanently damaged you know, after a few months in space if you if you have any emergencies up there you have to perform stuff on yourself, especially for dental emergencies does not sound great. I think we went through admitted administrating anaesthetic to yourself in your mouth and being able to kill yourself as well. Because the the nerve where you’re where you have to insert it, it’s very close to another variant that might end up ending your life. So it is it is, you know, terrifying and yet I really want to go? It’s just that the whole thing that every astronaut comes back with saying, you know, completely changed their view of Earth. You just being able to see it from such a distance. And after did your flights as well floating is very fun. To be able to just float in space.

Ria: I wish you all the best and please, clean up space for us. Thank you, Zaria.

If you found this interview to be informative, you can explore more current space news, exclusives, interviews and podcasts here.

Share this article: