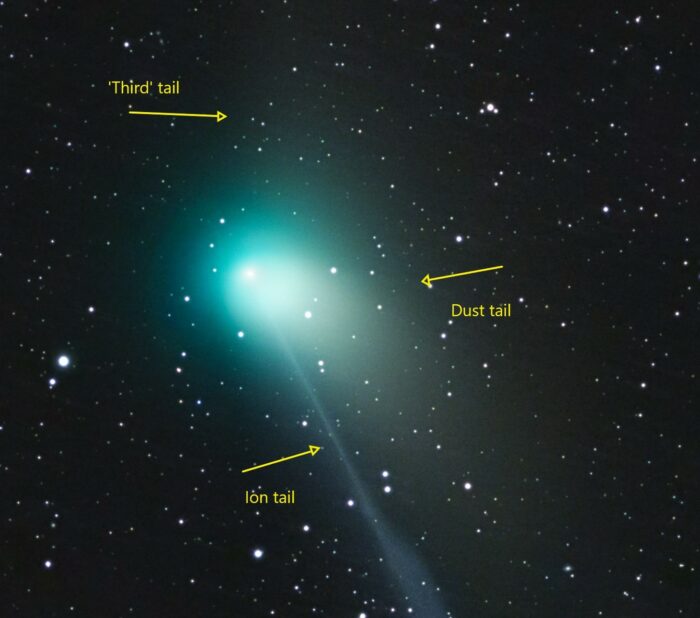

Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF), a visitor from our outer solar system, has reached its perigee (closest approach to Earth) yesterday. The green comet, discovered in March 2022 by astronomers Frank Masci and Bryce Bolin in California, USA, will stay visible to the naked eye under the right dark sky conditions for the coming days. Comets usually appear in the sky unexpectedly and are only observable for a short duration of time. Why is this? What are comets made of and where do they come from?

Parts of A Comet

The head of the relatively small cometary body (nucleus) is called the coma. The rather porous nucleus is composed of water-, carbon dioxide-, ammonia- and other ices as well as solid dust particles, mainly silicates. A comet owes its extensive tail to these ices being heated up as the comet approaches the sun at distances less than 3 astronomical units, or approximately 4.5 x 108 kilometers. The ices sublime (turn directly from solid to gas) and carry the dust particles along with them to form the cometary tail.

The size of the low density nucleus can range from a few kilometers or a few tens of kilometers across, while the coma and tail structure can reach hundreds of thousands, or millions of kilometers in size. In addition, cometary tails have two parts: the ion tail and the dust tail. The ion tail comprises ionized gases emitting light while leaving the nucleus, while the dust tail reflects and scatters sunlight.

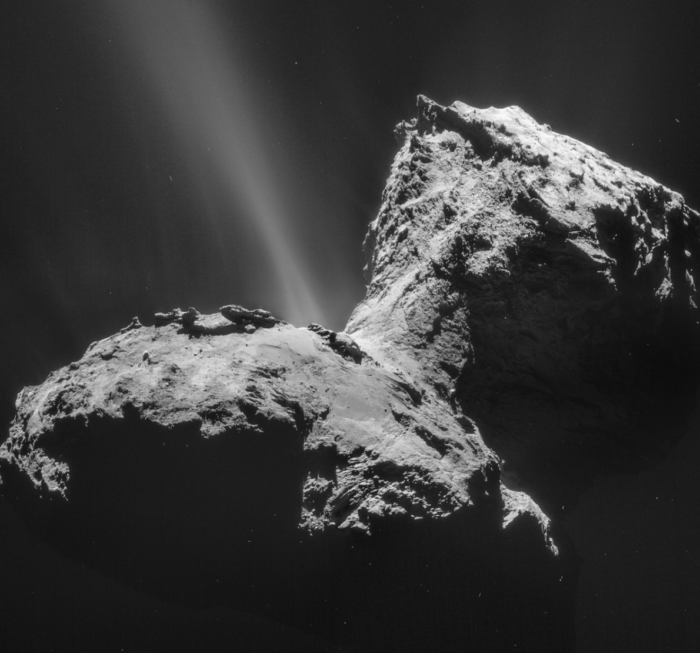

As comets eject gas and dust, they lose mass and can occasionally split and fragment. Due to this process, their lifetime is fairly short once they enter the inner solar system. However, two originally separate nuclei may undergo amalgamation, resulting in a bigger structure, just like in the case of comet 67P/ Churyomov-Gerasimenko.

A cometary nucleus cannot release gas from its entire surface as after the surface ices sublime, a layer of dust remains, shielding the ices beneath from direct sunlight. Areas with exposed ices are called the active regions, accounting for at least 90% of the gas and dust output of the celestial body. Holes in the surface and landslides may trigger jets and degassing, respectively.

Icy Origins

The comets’ ice content is due to their origins: these planetesimal bodies are remnants of planetary formation during the process of accretion (the growth of bodies as a result of collisions), from the solar nebula (a cloud of gas and dust from which our solar system formed). Comets most likely formed in the outer solar system, where the giant gas planets are, or even further out in the Kuiper Belt, which is beyond the orbit of Neptune, containing about 10 billion celestial bodies. These were the regions of the solar nebula where temperatures allowed ices to exist.

While some comets were thrown into the inner solar system, perhaps colliding with the newly formed rocky planets, others were ejected from it. These comets, outside our solar system, formed a cloud of comets, called the Oort cloud. This spherical cloud is estimated to contain around 10 trillion comets with a total mass of about 25 times that of Earth.

Comets are scientifically significant due to their relatively unaltered accreted material and not being subject to gravitational compression. Comets therefore, offer a window into the original composition of our solar nebula. Furthermore, compounds found on the surface of cometary bodies may hold the key to the ingredients of life.

Eccentric Orbits

Long-period comets come from the Oort cloud and have very long orbital periods. These comets can enter our inner solar system from any direction and at any time. They are unpredictable, just like comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF). Long-period comets could impact Earth at speeds at around 72 kilometers per second.

Short-period comets, on the other hand, have an orbital period of less than 200 years, with large eccentricities. They originate in the Kuiper Belt, and their number is replenished by orbital evolution of other celestial objects in the Belt. Sometimes, even long-period comets can become short-period ones if gravitationally captured during a close approach to Jupiter. Short period comets may collide with Earth at speeds of about 20 kilometers per second.

Hard to Predict

Cometary positions are difficult to predict as the outgassing can happen in any direction, slightly altering the object’s orbit. These non-gravitational forces either slow down or speed up the comet in its orbit. Although collisions with comets are possible, the solar system’s gas giant planets provide shielding against them, especially Jupiter. Comets may impact Jupiter before even making it into the inner solar system, or they can be scattered back to the outer solar system straight away.

Featured image: Comet ZTF and its apparent three tails. Credit: Oscar Martín (startrails.es)

If you found this article to be informative, you can explore more current space news, exclusives, interviews and podcasts here.

Share this article: